By Michael Kuhne | October 20, 2016 | AccuWeather.com

In an age where human lives are increasingly dependent on electricity, computers, satellites, GPS and digital communication systems, the threat of space weather has become an increased concern for government officials around the world. Powerful solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) can devastate the world's interconnected power grids, airline operations, satellites and communications networks.

However, with recent advancements from researchers at the University of Michigan and Rice University, NOAA will be able to issue the first operational, regional forecasts to help mitigate the risk that solar storms pose, according to Dan Welling, assistant research scientist in the U-M Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering.

When a geomagnetic storm interacts with the Earth's magnetic field, it drastically changes the planet's magnetosphere, and in turn generates powerful electric currents in the ionosphere that are thousands of amps.

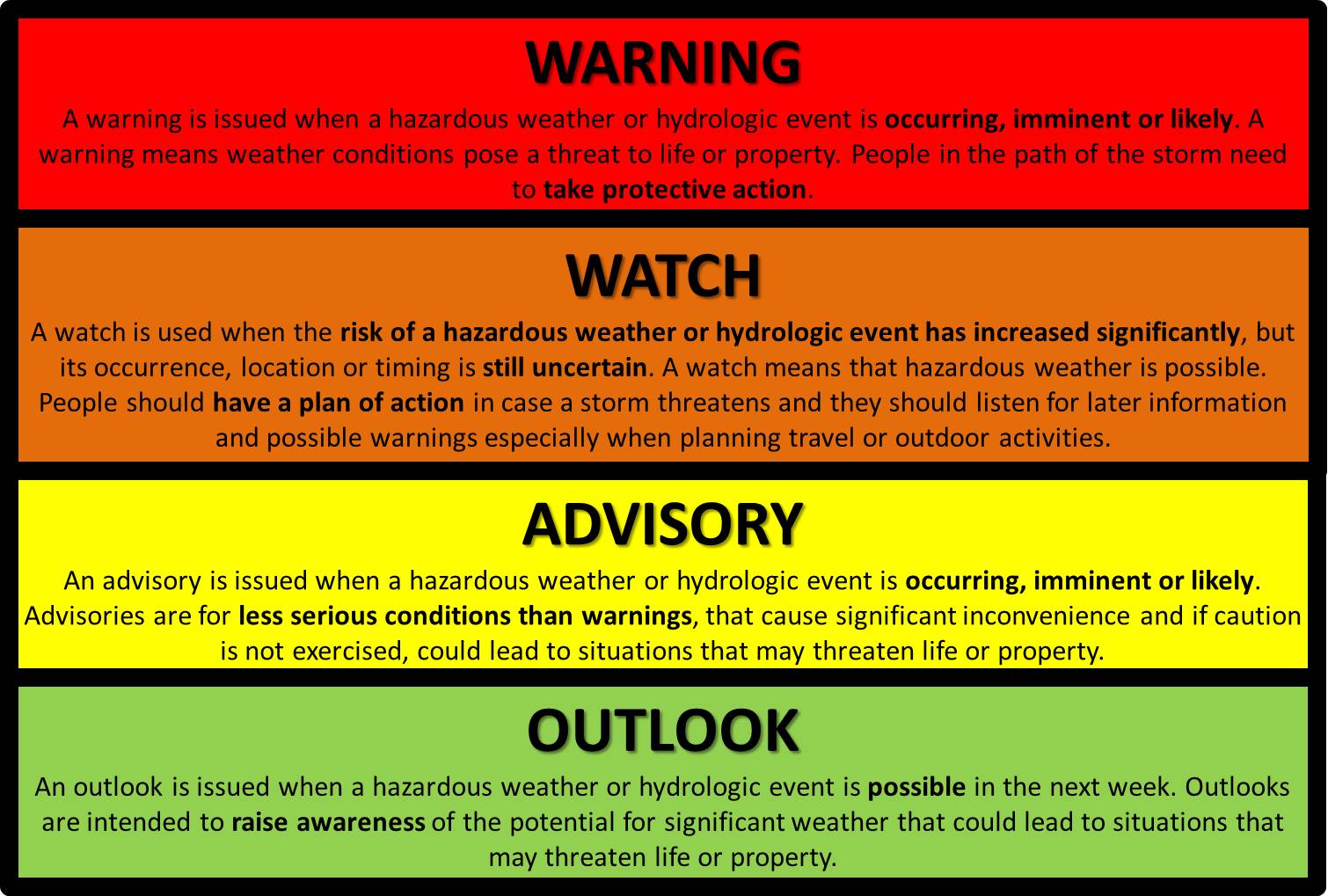

These currents are mirrored in the conducting Earth as geomagnetic induced currents, where critical electrical infrastructure is grounded. The magnitude of these storms are rated on a scale similar to tornadoes and hurricanes at G-1 through G-5, with the latter being the highest magnitude.

"In some worst case scenarios, the damage could be extensive and take weeks to months to fully recover from," NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center director Thomas Berger said last year.

"One of the most pessimistic views and estimates was produced by the National Academy of Sciences in 2008," Berger said. "It has numbers in the $1- to 2-trillion range with full recovery taking 4-10 years."

While predicting space weather impacts has proved challenging in the past, for the first time in NOAA's history, regional forecasts can be made to warn utility and satellite companies in advance with the refinement of the new geospace forecasting model.

"They key thing is that for the first time we can provide the actionable guidance [regionally] that they need," NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center's Chief Scientist Howard Singer said.

Singer said that the model provides forecaster guidance for alerts they issue to help better protect critical infrastructure during a potentially damaging space weather event.

NOAA placed the new model into operation in early October, which Welling said is a "huge step" moving forward for space weather forecasting. NOAA can now issue regional forecasts that provide unique data for each 350-square-mile plot of Earth, with up to 45 minutes of lead time for utility companies prior to the storm hitting.

While this may be a giant leap in space weather prediction, Welling said that the common dialogue among researchers is that space weather is still 50 years behind traditional weather forecasting.

Even with the challenges researchers must overcome in the future, a 30- to 45-minute lead time is still a great advantage to many of the utility officials Welling has spoken with during his work on the geospace model.

Welling added that the lead time provided by the geospace model offers enough time to take action and mitigate long-term impacts.

According to Singer, utility companies can perform a number of tasks to mitigate problems, including monitoring their systems in advance, changing the way power is shared and load shedding in order to prevent stressing their grids.

NOAA's new geospace model is comprised of three different components that provide the data needed to issue a regional forecast, according to Welling. Collectively, it pulls together and combines its data by simulating the effects of Earth's electric and magnetic fields as well as an independent ionosphere model, and a model developed by Rice University that combines data from the "ring current," a collection of particles that flows around the planet during space weather events.

While the sun is currently approaching a decline in the solar cycle, scientists have estimated that there is up to a 12 percent chance that Earth could be hit with an extreme solar storm in the next decade, according to the University of Michigan.

In 2012, Earth experienced a near miss of a storm that could have been near the magnitude of the historic 1859 Carrington Event, and in March 1989, a geomagnetic storm left nearly 6 million people without power for more than nine hours in Quebec, Canada.

This increased awareness of the potentially devastating impacts space weather poses to civilization prompted President Obama to sign an executive order on Thursday, Oct. 13.

"We have had meetings with FEMA to brainstorm [what actions can be taken during a space weather event]," Singer said, adding that President Obama's latest directive is all part of the increased awareness of the potentially disastrous impacts space weather can pose to large portions of the globe, unlike isolated weather incidents which impact small regions of the planet.

"This order defines agency roles and responsibilities and directs agencies to take specific actions to prepare the Nation for the hazardous effects of space weather," according to the White House document. The document stated that extreme space weather events could result in cascading failures of vital services and simultaneously affect and disrupt health and safety of people across entire continents.

"It's just a start, but there will be a lot more we will be able to do in the future," Singer said, citing advancements in NOAA's capabilities and the new geospace model's ability to provide better specifications on the interactions with Earth's magnetic field.